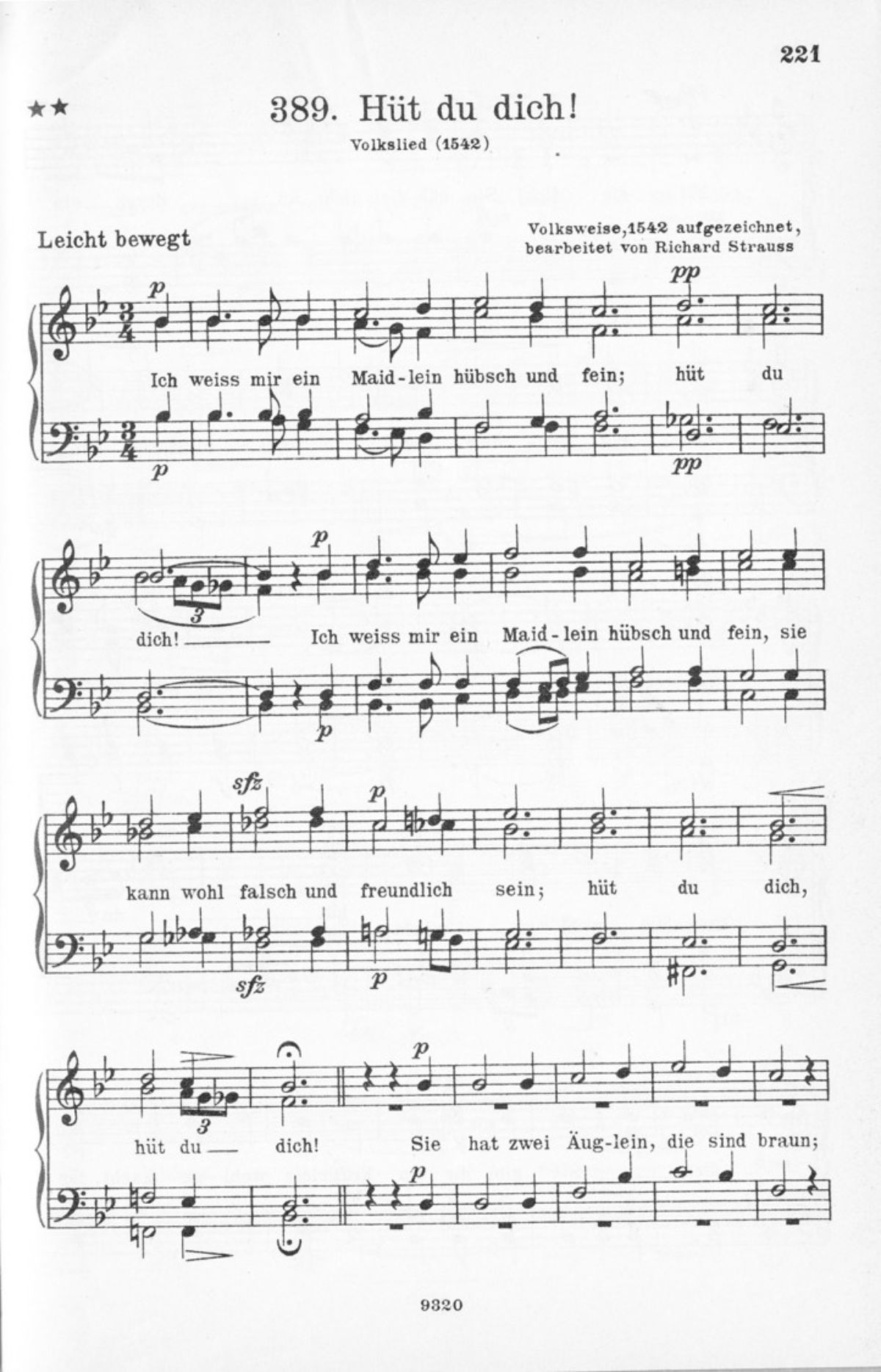

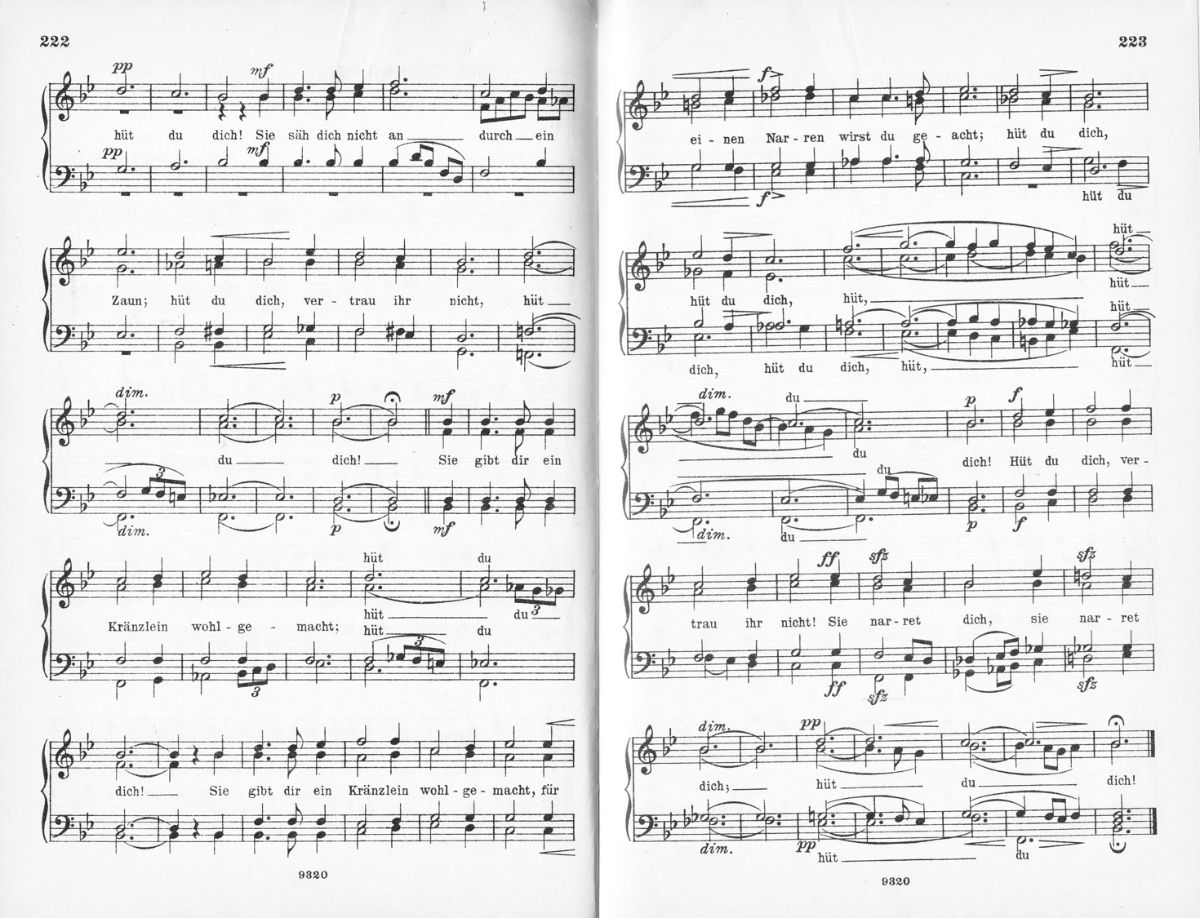

Strauss was considered to be one of the leading anathemas of the Romantic style. Typical for this is Paul Kickstat's condemnation of this arrangement when he wrote in 1931 that it represents a "purely artistic juggling with the folksong", and further that its

- melody is truly shaped into a choral art song of a highly Romantic nature. The art and skill of the arranger degenerates into mannerism. In spite of the extreme effort to write independent voices, all of the harmonic effects indelibly mark this air as a concert or virtuoso piece [9].

Apart from the harmonies themselves, which were not a subject of discussion, two aspects of this arrangement would have been considered decadent, unrelentingly Romantic by members of the Jugendmusikbewegung. The first is the homophonic harmonic style, which one attained best by accompanying the melody in thirds or sixths [10]. Walter Hensel characterized this style as being sentimental [11].

The second aspect is the care taken in marking the dynamics, particularly as evidenced at the end of the piece. Jöde opposed this approach, writing that as the dynamics are an automatic result of the association of the melodic line with the text, the only thing one needs to do is

- make sure that the linear musical values do not in any way overstep a minimum that could cause damage, so that, for instance, an occasional crescendo or decrescendo must result solely from the architecture of the entire structure, but never may be applied subjectively for poetic reasons [12].

The adamance with which this manner of performance is rejected makes one wonder what these leaders of the Jugendmusikbewegung were really talking about. Luckily we have one specific reference to the Thomanerchor from 1926 in which Konrad Ameln complains about the frequent changes of tempo and strong alteration of dynamics, how they disturbed the "polyphonic framework of the piece"; in addition, the "quiet flow of the events" was often ruined by a "racing, nervous drive [13]." There is a recording available online of In Dulci Jubilo, a 14th-century Christmas song, made by this choir in 1930 which I think this eloquently demonstrates what Jöde and Ameln were talking about [14].

Arnold Schering also spoke in 1931 of the necessity of having faster and more consistent tempi, going so far as to say that the conductor at that time had "no other function than that of a living metronome [15]." Although he was disdained by members of the Singbewegung as someone favoring a subjective approach to music [16], Schering's advocation of a tempo of around MM 80 for the semibreve matched theirs, musically and aesthetically:

- All dissolution, ambiguity, subjectivity is thereby eliminated in advance. Even the music of the a capella singers in the 16th century, which in the eyes of posterity seems to float in the higher spheres, has its feet firmly on the ground in this regard. Where a accelerando or ritardando was desired, it was written into the music in such a way that in spite of a continual, steady beating of the tactus it seemed to happen automatically [17].

Once again it is perhaps good to put this into perspective with the performance practices of the time with which they were contending. There is a recording online of the Johann Strauss Orchestra performing Lobe den Herren with a large choir in 1913. For your information the metronome marking is MM 49-50 [18].

The musical aesthetic also became characterized by a certain "objective" sound quality as early instruments became popular during the 1920's. Indeed representatives of the Jugendmusikbewegung, instrument makers, professional musicians and musicologists in a meeting in 1930 spoke of "the transformation of the sound ideal from a thick, loud, spongy sound to a clear, precise, focused one, from color to line [19]." The "characteristic, quiet «non expressivo» sound [20]" of the recorder was seen to be particularly suitable for polyphony, as

- the recorder player can only bring his instrument to the essence [of the matter] if he is prepared – by placing his own personal expressive desires to the side – to serve the sound. By striving after this sound and timbre, he relinquishes the expression of his feelings and overcomes that which is most personal to him. In that he serves the sound, he serves something objective. And it is just through this intent to serve the objective that he creates also the basis for a community [21].

The rigid, static quality of the recorder or old flutes and oboes was seen as being more appropriate for this music than the dynamic and expressive possibilities of modern instruments. This quality was then taken as a model for stringed instruments. Arnold Schering gives a description of this model in his book on performance practice:

- One bowed the instruments [....] with a quietly guided bow, regular in timbre and without accents, so that the sound flows on continuously and softly like a recorder [22].

and further in a footnote:

- This playing without pressure and accentuation, which comes equally from the construction of the instruments, the peculiarities of the old bow and the stringing, is difficult for our modern players and is only attained after much practice with great self discipline [...]. By putting on a mute, the harshness of the modern instrument can be softened [23].

Or as Walther Pudelko wrote in the concluding remarks to his edition of five pieces by Dowland for stringed instruments:

- A long, quiet bowing and the greatest discretion in vibrato will best match the sound of the viol family. Any soloistic impulse must be destructive, and even then, when an individual voice or the whole structure cries out for expression and intensification, one may not use today's style of playing to breach the limits of the integrity [of the whole [24]].

Thus through the gradual introduction of instruments, first as an adjunct to the vocal polyphony, and then in their own right, the aesthetic ideals of purity and objectivity came to be associated with all of early music, not just with the polyphony of the 15th and 16th centuries. Instrumentalists were expected to cultivate the same abstract sound as the vocalists, and for the same reason: through objectivity one created a sense of community, created the sense of direct contact with the music for those immediately involved.

There are unfortunately no recordings from this period of groups associated with the Jugendmusikbewegung, a fact that no doubt has to do with their scruples about singing for audiences, for people who did not take part in the actual act of making music. What is striking, however, is how many of the above descriptions have been negative, speaking out against what is not wanted, not just simply stating – as we find in most of the treatises of earlier times – how something is to be done.

I think this reflects the attitude of those attempting to change the musical conventions, the performance habits of decades, an enormous task. It is only under such circumstances that August Halm, the musician and pedagogue who served as the figurehead of the educational, reformative portion of the Singbewegung, could answer to the question of how the performer should proceed when faced with the decision of how to phrase in the following manner:

- He shouldn't phrase at all, for he in particular should not decide. The theme wants to be played as it is written, thus in a manner where no phrasing, not even an undoubtedly correct one, is forced upon the listener [25].

On one level this goes to the opposite extreme, is an attempt to reduce the Romantic effulgence of personal interpretation to nothing. This is, of course, an impossibility, as the decision to perform without Romantic expressive devices is also an expression of individual taste. But in connection with the recordings mentioned above it can perhaps be understood as a very human reaction: if too much is bad, then none must be good. Furthermore, it is in line with Richard Taruskin's comments on modernist historical reconstructions where "the artist trades in objective, factual knowledge, not subjective feeling. His aim is not communication with his audience, but something he sees as a much higher, in [T. S.] Eliot's words "much more valuable" goal, communion with Art itself [26]."

Konrad Ameln, however, expressed this desire for objectivity in a more positive manner, suggesting that the music should be in the forefront of a performance, rather than being a reflection of the personality of the performer in his comments on a presentation of Leonard Lechner's Passion according to St. John:

- What made this performance particularly valuable for [him] was the circumstance that the choir was successful to a high degree in singing objectively, that is avoiding any investment of personal feelings or personal agitation, so that the choir, or better said its members, did not sing from themselves, but rather let it sing and only served as instruments [for the music]. The singers themselves will be most aware how far they really succeeded and how much we all still have to overcome various inhibitions for a perfect rendering of polyphonic works [27].

I hope, however, that it has by now become clear that a large portion of the aesthetics of most historically-informed performances of 15th- and 16th-century (and later) music on the Continent, as well as the interest in this earlier period, was a result of a romantic rejection of Romanticism and all that was perceived to be connected with it.

We, and I include myself in that we, then in the second half of the twentieth century turned this rejection into perfection: perfect intonation, perfect togetherness, absolute beauty, leaving out the all so important question about what this music was intended to say, to express. We did this with the virtuous feeling that we were being true to the past, bringing the music of earlier centuries back to life in accordance with the "rules" of performance practice of those times, being fully unaware (and again I include myself among the ignorant) that what we were really doing was carrying on and developing the anti-Romantic aesthetic of the early twentieth century. In our naïveté and excitement and passion for the beauty of this music, we were able to blank out the influences of our own culture on our ideas of how it should sound, we were certain that we being true to the intent of its composers. I wish, however, to encourage an increasing awareness of the influence our own society, our own culture has on our musical decision-making. Openly acknowledging this would in turn – speaking ideally – stimulate greater creativity in interpretation of the sources, as they would increasingly gain the function of tools by means of which we search for greater understanding of the music which we then knowingly perform within our own cultural context.

At the same time this acknowledgment would enable us to perceive and investigate the parallelism in time and space of this "objectivist" musical aesthetic with the "modernist" one of Stravinsky. Although the latter arose in a different cultural context, had sway with other musicians, the one complements the other. Both of these movements were seeking a "new" music, one lacking the nimbus the Romantic era. Neue Sachlichkeit sought novelty through the creation of new objective works, music suitable for modern ears. The Jugendmusikbewegung, however, sought salvation through older music, as in the words of Gerardus van der Leeuw,"the quality of age is one of the most important means which enables art to express the holy [28]." Common to both were the desire for objectivity and clarity and the breaking away from traditional perception and analysis of music combined with a search for something new [29].

The music aesthetic of the Jugendmusikbewegung can thus be seen to represent not only the desire to break with the perceived evils of Romanticism, but also as the advocacy of an entirely new approach to music, for new sounds, for modernity. And thus Wilhelm Stählin was fully justified in his fears when he wrote in 1927 that

- Judicious leaders of the Singbewegung are themselves moved by the concern that they may get stuck in something aesthetic, that a new method or musical style could come from it [30].