Introduction

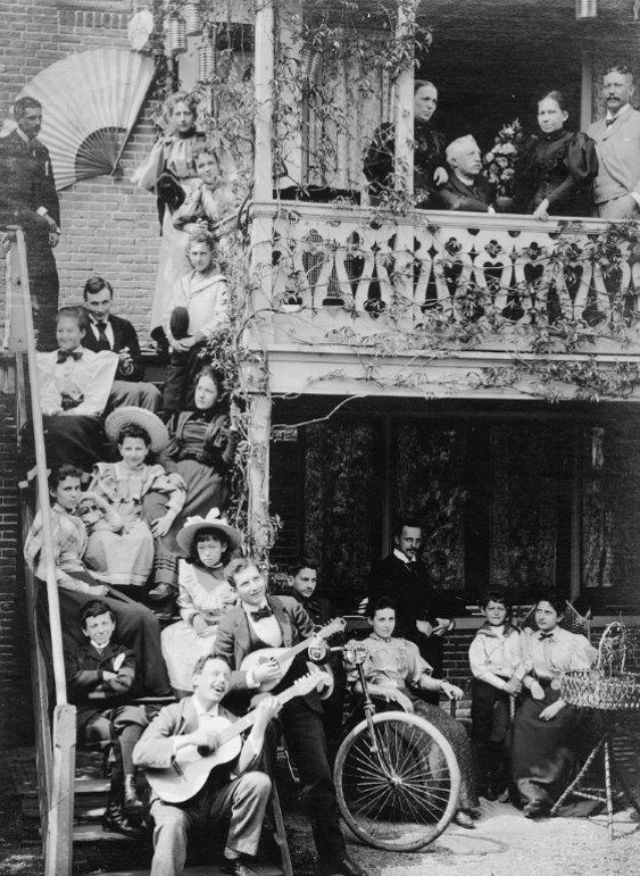

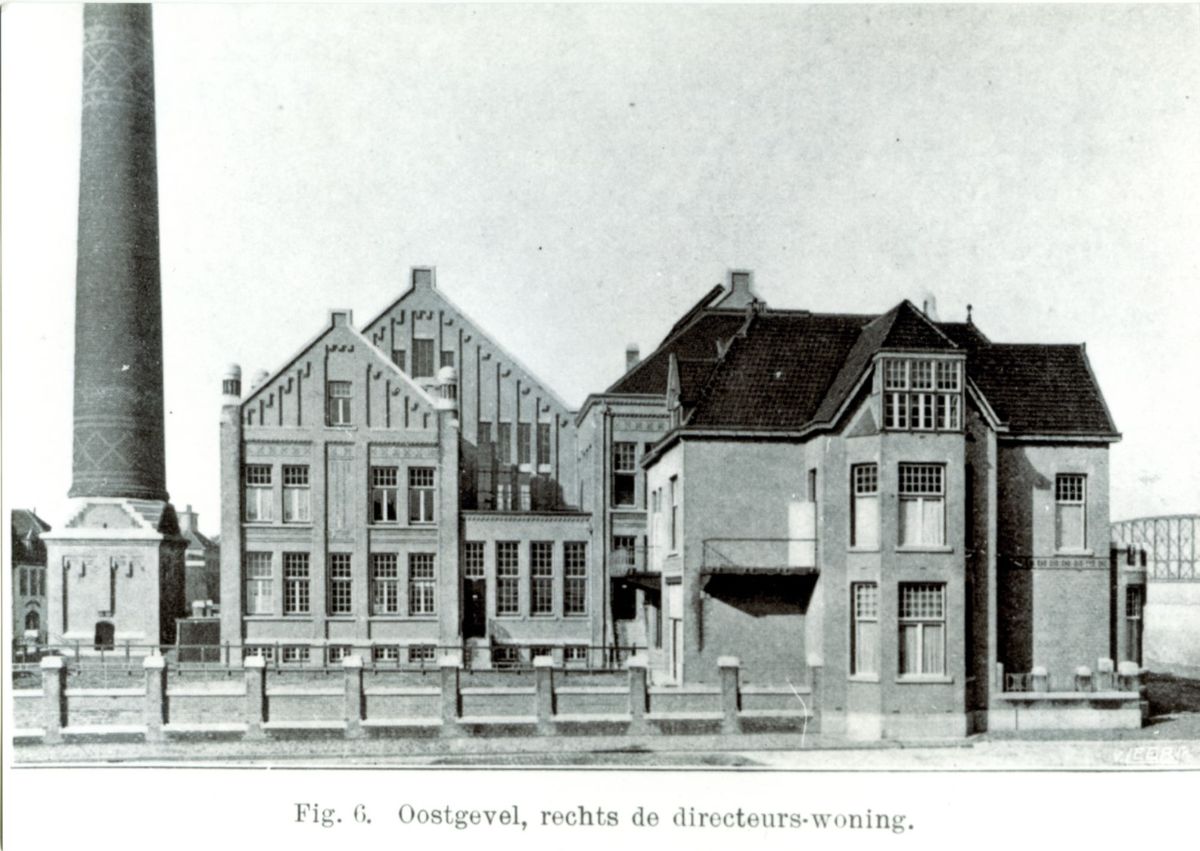

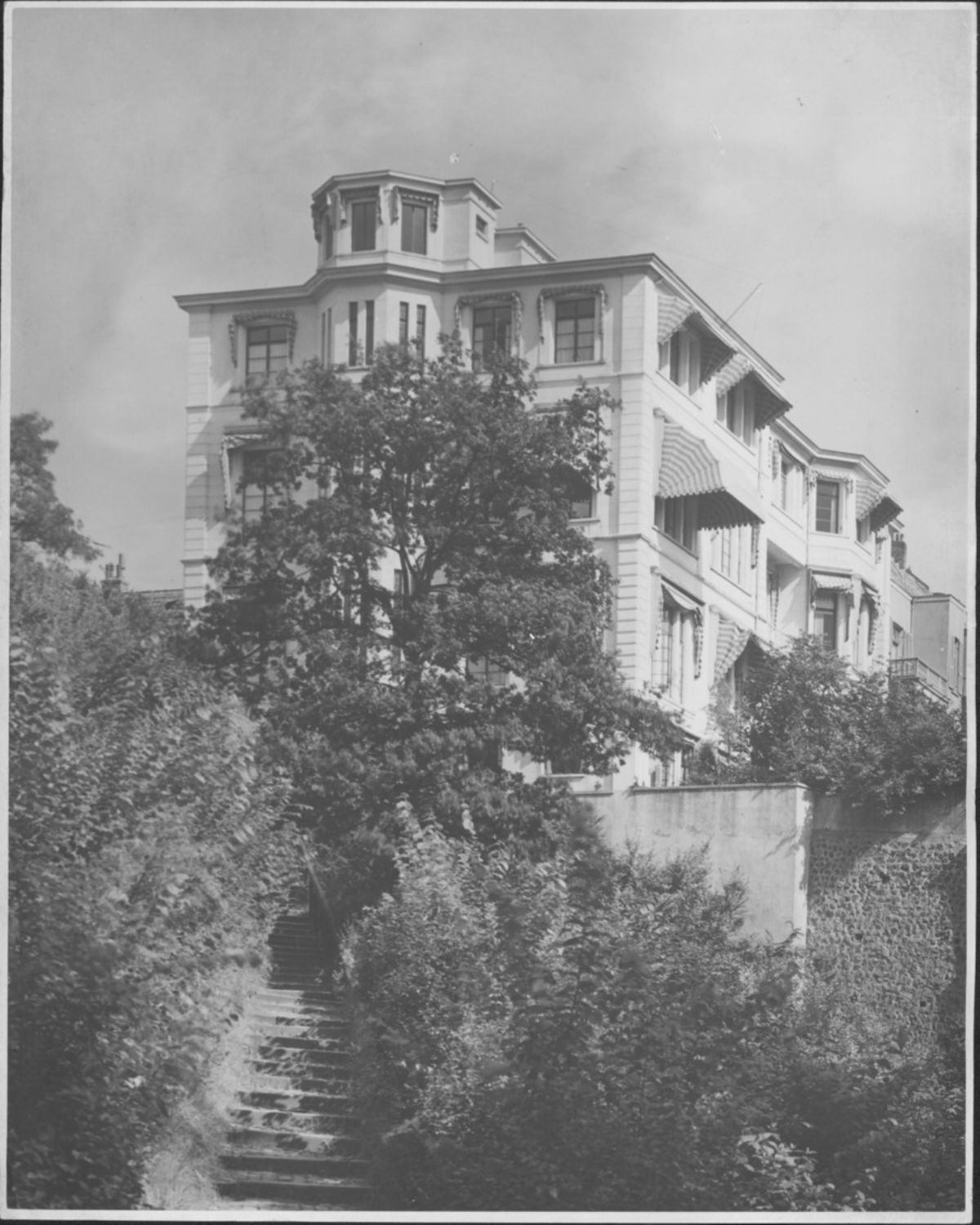

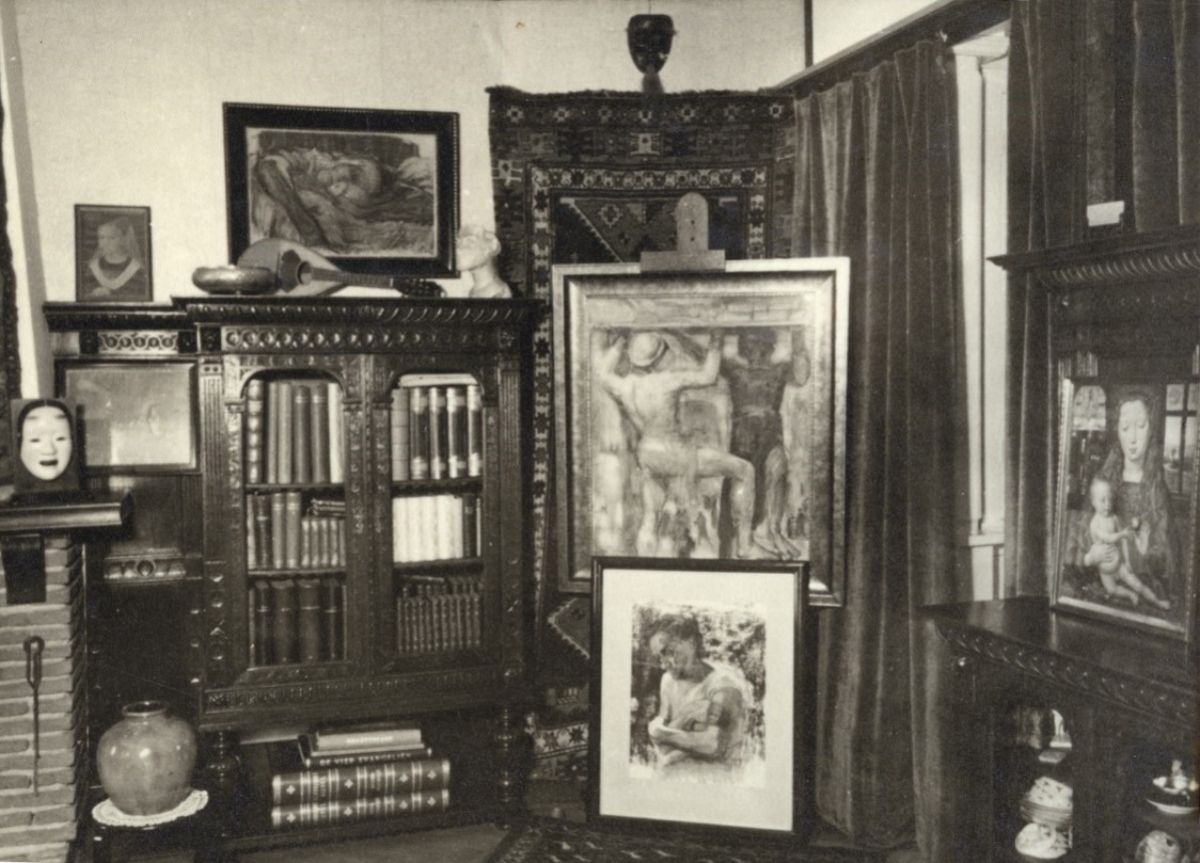

In order to understand Ina Lohr’s later path and her influence on the Early Music movement, it is necessary to examine her early musical education, the level of cultural discourse within her home. Her formal training at the Muziek-Lyceum in Amsterdam built upon this, its ideals and practices impressed upon her by the authority and stature of her teachers, Hubert Cuypers and Anthon van der Horst. Her musical intelligence and knowledge were immediately recognized in Basel in 1929, giving her the opportunity both in her role as assistant to Paul Sacher in regard to the Basel Chamber Orchestra, as well as a teacher at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis to put what she had learned into practice in her new environment. With Early Music next to that of the Modern Classic, Gregorian chant next to pre-Reformation sacred song, the boundaries were fluid, with one affecting the other. Following World War II she then returned to the Netherlands, passing on her new knowledge to a circle of musicians, eager to build not only upon her knowledge but also her innate ability to engage people in song. Her understanding of melody, as reflected in her method of solmization, thus came to have a significant influence on musicians such as Gustav Leonhardt, Jan Boeke, and Kees Vellekoop.

I need to begin today by thanking all of those who made this conference possible, starting with the Schola and the SNF. It was like a dream-come-true to be given the wherewithal — at the end of my official professional career — to devote the great majority of my time to my passion, to my obsession. Further, I need to express my appreciation to all the family members, the friends, and former students of Ina Lohr who have given me some of their time, shared with me their experiences with Ina Lohr, as they have given me a picture of her as a person that I could not have attained otherwise. Among these, I must particularly mention Christopher Schmidt, who not only studied with her in the late 40's, but later became her colleague at the Schola. We have spoken many, many times, analyzing the material I have found; his memories, his sense of the structure of the past have given me confidence in how I have knitted the documentary material together. And finally, I must express my gratitude to the Sacher Stiftung, and all the various members of the staff there who have been of great assistance to me, not only in enabling me to examine Ina Lohr's estate, but also in helping me to gain access to her letters to Paul Sacher; further they put me in contact with descendants of her father's family, and have given me many additional hints and suggestions as to where I might find further evidence of her activities. For the first time I really understand why prefaces to biographies contain pages and pages of acknowledgments!

Our project, Ina Lohr (1903–1983), an Early Music Zealot: Her Influence in Switzerland and the Netherlands, began with the goal of investigating Ina Lohr's life and work and illuminating it in the context of the Singbewegung and the music reform movements of the Catholic and Protestant churches, all phenomena which had their origins in the late 19th century. Their ideals of purity and simplicity can be shown to be a source for historically-informed performance practice in the twentieth century, particularly that of the 15th and 16th centuries. In addition, we wanted to delve into the question of how Ina Lohr served as a link between the Swiss and Dutch Early music scenes. The resulting picture is much more varied, more fascinating than any of us expected.

After four years of working on a project, after amassing mountains of material, it is difficult to decide which particular story to tell, which aspects to focus upon. Today we have chosen to highlight the Dutch influences upon her and her reciprocal influence on the post-war musical world in the Netherlands. After having heard about the contentious environment in both the Catholic and Protestant musical worlds during her youth, listened to the songs of two of her most formative teachers, as well as ones she wrote herself during her studies at the Muziek-Lyceum under their tutelage, I now have the job of tying these strands together into a coherent story. I will begin with her upbringing in the Netherlands and her formal training at the Muziek-Lyceum. I will then look at her time in Basel, primarily from the point of view of how her Dutch training not only affected the development of the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, but also at those portions of her experience there which came into play when she returned after the war to give workshops in Holland. In the process I hope to show how she — through her innate talents and abilities, but also through the vagaries of life— was a central link between some seemingly contradictory elements in the twentieth-century musical world, such as the movements to reform the music in both the Catholic and Protestant churches, between Early Music and New Music, between huismuziek and professional musical circles, and, of course between the Dutch and Basel Early Music scenes. Even as a student her main interest lay in sacred music, but as she developed personally, her focus turned increasingly to the question of how to revitalize Protestant church music, so that the congregation would once again be able to communicate directly to God as intended by the original instigators of the Reformation. Thus in the pursuit of her goals within the structures of the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis and, to a certain extent, the Basel Chamber Orchestra, she overrode these separatist distinctions, transcended them to fulfill her own particular spiritual needs.